In England…

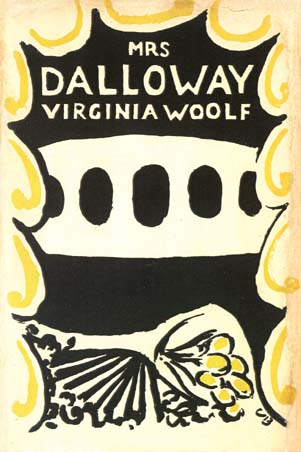

Virginia Woolf, 43, is anticipating the reviews for her fourth novel, Mrs. Dalloway, which she and her husband Leonard, 44, have just published at their own Hogarth Press, with another cover by her sister, Vanessa Bell, 45.

She has been working on it for the past three years, building on short stories she had written, and experimenting with stream of consciousness. The beginning of this year was spent on the rewriting, which, she had confided to her diary, was

‘the dullest part…most depressing & exacting.’

Leonard is enthusiastic. He feels it is Virginia’s best work. But he has to think that, doesn’t he?

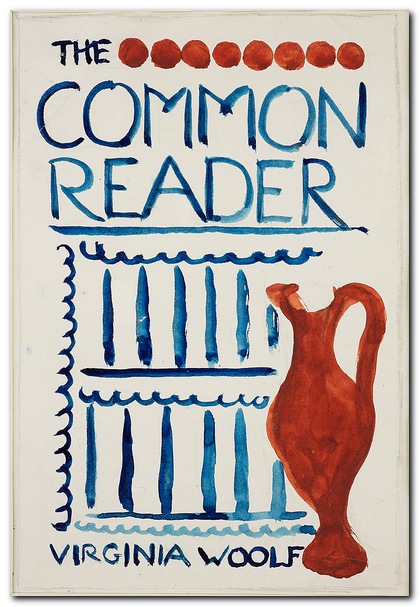

Last month, the Woolfs had brought out a collection of her critical essays, The Common Reader, also with a Vanessa cover. Virginia had worried that it would receive

‘a dull chill depressing reception [and be] a complete failure.’

Actually, there have been good reviews in the Manchester Guardian and the Observer newspapers, and sales are beginning to pick up a bit.

The ten-year-old Hogarth Press is doing quite well, having survived a succession of different assistants. They had published 16 titles the previous year and are on schedule for more this year. In addition to writing their most successful works, Virginia has been closely involved with the choice of manuscripts among those submitted by eager novelists and poets, as well as setting the type. She finds it calming.

Despite the stress of a new publication, physically Virginia is feeling quite well. She and Leonard have been busy in London with Hogarth, but also getting out and about with family and friends. Fellow writer Lytton Strachey, 45, had praised The Common Reader, but thinks that Mrs. Dalloway is just

‘a satire of a shallow woman.’

Virginia noted in her diary,

‘It’s odd that when…the others (several of them) say it is a masterpiece, I am not much exalted; when Lytton picks holes, I get back into my working fighting mood.’

Virginia’s literary competition with Lytton—he has always outsold her—is motivating her to get to work on her next major novel. She’s thinking of writing about her childhood, and the summers the family spent on the Cornish coast.

In France…

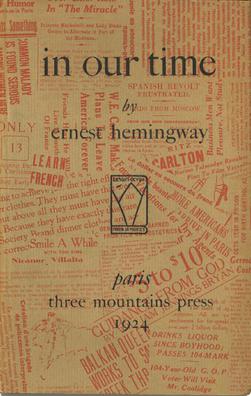

Ernest Hemingway, 25, is regretting having snapped up the offer from the first publisher he’d heard from, Boni & Liveright. He’d been so thrilled to get their letter when he was skiing in Austria that he’d accepted the next day. His first collection of stories and poems, in our time, had been published last year by Three Mountains Press, a small company operating on Paris’ Left Bank. But Boni & Liveright was a major American publisher who wanted to bring it out as In Our Time and have first shot at his next work.

When he’d returned with his wife, Hadley, 33, to their Paris apartment there were wonderful letters waiting for him from Maxwell Perkins, 40, senior editor at rival publisher Scribner’s.

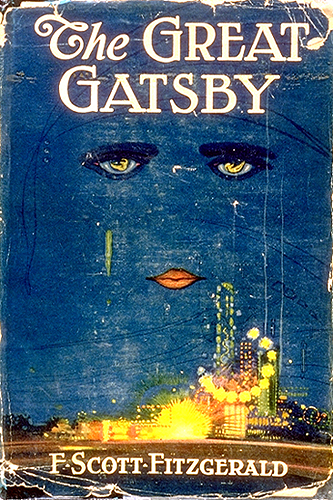

In addition, Ernest has just met one of Scribner’s top authors, F. Scott Fitzgerald, 28, who had recommended him to Perkins as long as a year ago. Fitzgerald was happy to share with Hemingway his inside info about the world of New York publishing, telling him that Scribner’s would be a much better choice than Boni & Liveright.

However, that first meeting with Fitzgerald in the Le Dingo bar hadn’t impressed Ernest much. Scott had been wearing Brooks Brothers and drinking champagne, but he kept praising the poems and stories of Hemingway’s that he had read, to the point where it was embarrassing. Then he asked Ernest whether he had slept with Hadley before they got married, turned white, and passed out. Ernest and his friends had rolled Scott into a taxi.

But on their second meeting, at Closerie des Lilas, Fitzgerald was fine. Intelligent. Witty. Interested in the Hemingways’ living conditions—in a rundown apartment without water or electricity above a sawmill on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. Ernest decides it might be alright to take his new friend to the salon he frequents at the home of another American writer, Gertrude Stein, 51, and her partner, Alice B. Toklas, 48, on rue de Fleurus, near the Luxembourg Gardens. Gertrude hates drunks.

Scott had asked Ernest to come along on a trip to Lyon to recover a Renault he had had to leave at a garage there, and Hemingway is thinking of going. After all, Fitzgerald says he’ll cover all the expenses.

His latest novel, The Great Gatsby, published by Scribner’s just last month, is not doing as well as Scott and his wife Zelda, 24, had hoped. Selling out the first print run of almost 21,000 copies would cancel his debt to his publisher, but they are hoping for four times that.

He has discovered that Perkins’ cable to him claiming that the early reviews are good had been a bit optimistic, and sales aren’t going great.

Scott is worried that he is reaching his peak already.

In America…

Perkins is writing to Fitzgerald,

‘It is too bad about Hemingway,’

regretting losing a promising novelist to a rival.

But he’s even more concerned about the mixed reviews for Fitzgerald’s Gatsby. The New York Times has called it

‘a long short story’;

the Herald Tribune,

‘an uncurbed melodrama’;

and the World,

‘a dud,’

in the headline no less. Even H L Mencken, 44, who can usually be relied on for some insight in the Chicago Tribune, has dismissed it as a

‘glorified anecdote.’

And FPA [Franklin Pierce Adams, 43], the most widely read columnist in Manhattan, says it is just a

‘dull tayle’

about rich and famous drunks.

However, FPA is not known for fulsome praise. Back in February he had prepared the readers of his Conning Tower column for the launch of a new magazine, The New Yorker, by saying that

‘most of it seemed too frothy for my liking.’

He didn’t mention that he had written some of the froth to help out his friends who were starting the publication. For the past couple months he’s been going weekly into the magazine’s shabby office to choose the poetry. There have been some funny pieces by one of his own discoveries, Dorothy Parker, 31, but he doesn’t give it much hope of lasting.

By now, sales of The New Yorker have gone from an initially respectable 15,000 to about half that. And the founder-editor, Harold Ross, 31, has had to cut the size to only 24 pages to save money.

But FPA can’t be bothered worrying about his friends’ losing business ventures. After finishing off a bad marriage earlier this year, he’s getting married!

Parker, Ross and all the others who gather for lunch at the midtown Algonquin Hotel daily, and for poker there weekly, have ventured out to Connecticut for the wedding.

Just yesterday, Ross’s chief investors decided to pull the plug on the magazine. Why throw good money after bad?

But, discussing their decision at the wedding, Ross and his main funder, Raoul Fleischmann, 39, start thinking that it may be too early to give up. Raoul says he’ll cough up enough to keep The New Yorker going through the summer, and then they can decide.

At the end of the day, FPA and his bride head back to the city, and he goes, as usual, to his Saturday night poker game and loses the money saved up for their honeymoon.

Donald Brace, 43, co-founder of Harcourt, Brace & Co., isn’t worried about funding, but he is anticipating reviews of two books he has just published: Virginia Woolf’s essays, The Common Reader, and novel, Mrs. Dalloway.

They have had success with Woolf before, but this is the first time that publication is simultaneous in the US and the UK.

The New York Times has raved about both Mrs. Dalloway and The Common Reader, comparing Woolf’s essay style to that of Lytton’s.

The Saturday Review of Literature calls the novel

‘coherent, lucid, and enthralling’

and wants her to write a piece for them about American fiction.

Virginia and Leonard will be pleased.